HERE, THERE, AND EVERYWHERE, The Universe, All Months, All Years — Once we had mix tapes. Then mix CDs. Now we have playlists.

Earlier this month, as I finished writing an essay I was reminded of that unique satisfaction that comes from curating the soundtrack to our lives. I’d been wrestling with that essay for months. In fact, I didn’t even know it was going to be an essay until it ballooned from a quick newsletter introduction into a five-thousand-word-long meditation on past imposter syndrome and depression.

The past is always knocking incessant Trying to break through into the present We have to work to keep it out But I won’t be the first to shout ‘it’s over’ -Billy Bragg, “Brickbat”

I struggled to cram the piece into this newsletter, then suddenly realized it didn’t belong here. If I wanted to write what I thought I needed to say, it needed to be an essay. It worked best as an essay. I also realized — and this is more important — that aside from the usual editorial shakedown, the piece was done.

I’d been surprised by how many emotions writing the piece had stirred up in me (I’ll wait to describe the piece in more detail until it’s published, if it’s published), and I was similarly surprised how suddenly I realized I didn’t need to fight the piece any longer. That realization prompted an almost physical emotional release.

Elsewhere in this edition: Ocean liner souvenirs, pensive dogs, reflected cities, and dam wars

As I basked in the realization’s afterglow I heard familiar guitar strums. A new song was beginning on my “Writing” playlist. Anticipating the song’s opening vocals I listened, mesmerized. I’d been listening to music all day, but it felt uncannily cued to the moment how this song began just as I saved and closed my file.

“I ought to leave enough hot water/For your morning bath, but I’d not thought…” concedes Billy Bragg as his 1996 “Brickbat” begins.

I first heard “Brickbat” about twenty years ago after I bought Bragg’s three-CD compilation, Must I Pant You A Picture: The Essential Billy Bragg, from Bull Moose Music in Portland, Maine. It’s been a staple on my ever-evolving writing playlist ever since, but this listening felt like my first. The song sounded newly relevant, as if conjured from nothingness by my circumstances.

Once “Brickbat” ended more perfectly-timed songs followed. I kept my computer on as I packed my things so I could keep listening. Each song resonated similarly with me. Each seemed quintessential to the moment in which it played. This playlist wasn’t simply entertaining accompaniment for my workday. That afternoon, in this world, in my life, the music was as essential as oxygen and light and blood.

I put down my bag, woke up my computer, opened a blank file, and started writing again. Not for this newsletter, nor my blog, nor a client, nor anyone. I just wrote. For me. For everyone. For you.

Can’t count to all the lovers I’ve burned through So, why do I still burn for you? I Can’t say -Sun Kil Moon, “Carry Me Ohio”

In 2015, the Welsh music historian Huw Spink blogged about “Brickbat,” explaining how it “isn’t an apology for domesticity,” but “a celebration.”

“This was, in Billy’s own words, a song about getting a life,” Spink writes. “The life that so many of his other songs documented the search for. For life, read love. Read, family.”

Through “Brickbat,” Bragg comes to terms with a slowing, a calming, a recognition of where he finds himself after the tumultuous years of protest and protest music for which he’s best known. A father now myself, that afternoon I recognized in “Brickbat” and the songs that followed the slowing of my life. Indeed, I recognized my “getting” of a life.

I also realized something about the energy I’ve expended over the years curating, adjusting, revising, and remaking this and other playlists. That realization? That I do so most fervently during life’s most intense moments, when assignments are due and deadlines careen toward me, or when personal and familial pressures mount.

In all such moments, survival seems to require superhuman strength and focus. Paradoxically, I find that strength and focus by redirecting my attention beyond the immediate need. In this essay’s case my only deadline was self-imposed, but the piece felt as urgent as any.

And don’t be so hard on yourself You won’t be better till your worse You won’t get better till you’re worse Yeah you, send a little love my way -Tegan and Sara, “Don’t Confess”

My attention and focus refreshes when not emptied into my work. I don’t only turn to crafting playlists to regenerate my creative reserves, but music’s advantage is the way it serves as a connective thread that weaves memory and emotion into the physical plane. That manifestation of ephemeral thoughts into tangible arrangements of sound waves illustrates, at least to me, the transformational power of creativity. It reminds me how the best writing carries similar conjuring power.

My writing’s obviously imbued with contemplation of “THE PAST.” Usually that’s the more general, removed past of “history,” but it’s also replete with my past, with memory. So too, I think, are the songs that appear on my writing playlist. They remind me of pasts private and public. Often they remind me of previous moments of intense writing and work, and think they help me attempt to regain those moments’ intensity, or at least, build upon it.

Sit Back, no song is written It’s nothing you thought of yourself It’s just a ghost, came unbidden To this house -Okkervil River, “Another Radio Song,”

That moment when I finished my essay and sat captivated by my playlist occurred amid the uneasy aftermath of the recent U.S. presidential election. For the second time in eight years an election left me heartbroken and concerned about the dark, uncertain days ahead. So much of my writing focuses on the stories we tell about how our society’s past shapes our understanding of the present. This time I finished my essay thinking less about the rest of the world’s history and more about my own past, how that past helps me understand who I am today, and how I might pursue the second half of my life.

As I write this I’ve been wondering why judiciously weighing which few dozen tracks provide the soundtrack of one’s day and meticulously ordering them into a specific sequence (or deciding to inject a little chaos and play them on “shuffle”) feels like such a critical task. It seems — again, at least to me — as important to one’s routine as filling a gas tank or remembering a laptop charger. Still, as important as I may find curating a playlist to be, I also wonder what influence focusing so much on the creative work produced by others while parsing one’s own creative dilemmas has on one’s creative process.

In our days we will say What our ghosts will say We gave the world what it saw fit And what'd we get? -Iron & Wine, "Resurrection Fern"

Doesn’t the atmosphere in which one produces one’s work impact that work’s dynamics? Isn’t there a risk that the fundamentally altering those dynamics might shift one’s work from what one originally intended? Much thought and analysis has explored the interplay of one’s creativity with the creativity of others, and how one’s creative output adapts to, is influenced by, and filters through the creative work one encounters.

That’s how inspiration works, right? So when we simply gather music we might want in the background are we stoking inspiration or muting it? I’m not sure, but I’m also not not sure. There must be some reason it feels so impossible for me to write without music playing, mustn’t there?

When “Brickbat” the memories stirred up by the essay I’d been working on swirled into an already-roiling maelstrom of thoughts about the election, the memories and emotions those thoughts evoked, a health emergency my dog faced, a host of other personal crises, and a paralyzing sense that lines that normally separated past and present — as well as interior and exterior worlds — were rapidly fading. I feared losing sight of the present and drifting into dark, murky waters churning with regret and anxiety, but “Brickbat” — and the songs that followed — reminded me of the reality and constancy of change

I saw something familiar in Bragg’s chorus, where he admits “I used to want to plant bombs/At the last night of the proms.” I never wanted to plant actual bombs, but when I was younger, more idealistic, and maybe a bit more radical, I’d absolutely wanted my words to be explosive. I wanted to shake up the comfortable existence into which so many of us seem lulled. Perhaps, I know I once thought, my work might even change the world.

I’d still thought something along those lines when I first bought that Billy Bragg collection in Maine even if I’d started growing out of that phase by then. But hearing “Brickbat” now was different. Among other things, I’m married, I have a kid, and I’m slowly coming to terms with the fact that the aging dog I needed to get home to that afternoon is ailing. Marriage and parenthood and pets don’t define me, but they’ve completely realigned me, as “Brickbat” suggests they had for Bragg:

Now you’ll find me with the baby, in the bathroom, With that big shell, listening for the sound of the sea I started crying as the trees began to sing. Light shone in on everything.

The past’s incessant knocking persists. We have so much work to do to keep it out, but our life is not over and our light has not gone out.

I love you. Yes. You.

You.

The yous that once were, the yous that might one day be, and the yous that are.

Now.

You.

I love you.

A playlist for the Scenic Route: The lyrics quoted throughout this piece come from “Brickbat” and other songs I’ve had on heavy rotation lately. I’ve put these — and other songs that, paradoxically, stop me in my tracks and push me through difficult times — on a playlist that I’ll send to anyone who buys a paid subscription at any level.

This week’s Souvenir

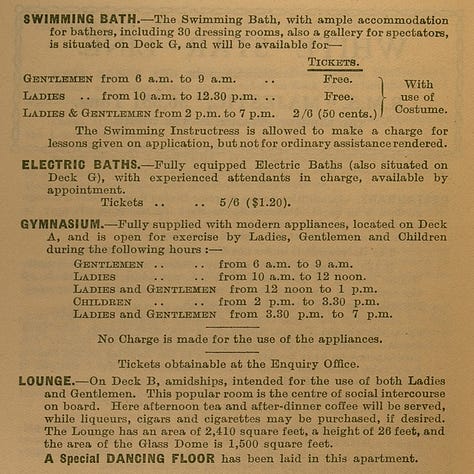

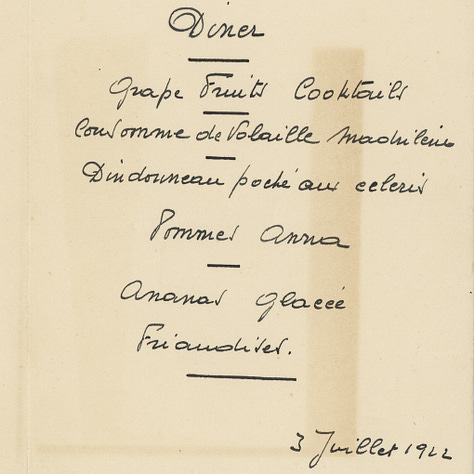

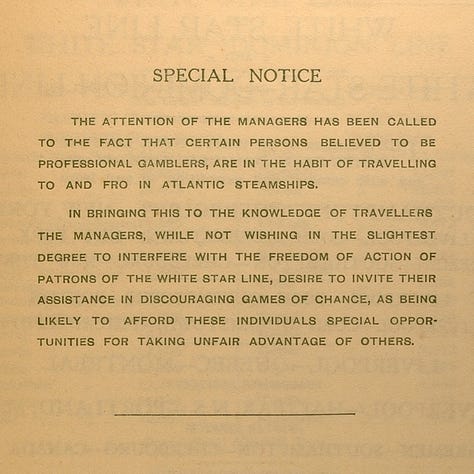

In 1922, my great-great-grandparents took three of their children on a months-long visit to Europe after stopping in New York City for their eldest son’s wedding (They also brought their first grandchild, Melville Jacoby, the subject of my books Eve of a Hundred Midnights and A Danger Shared, who was then five-years-old). They traveled first-class between New York and Europe on the largest ocean liners then sailing and visit such destinations as Vienna, Paris, London, Luzern and Pompeii. They also made an extended visit to Coburg, Germany, my great-great-grandfather Jacob Stern’s birthplace. I’ve been lucky to get a closer sense of the trip thanks to artifacts from the journey that Mel’s mother, Elza, and, in turn, my grandmother, Peggy, kept for decades. These include ephemera from their return trip aboard White Star Line’s RMS Majestic, which at the time billed itself as “the largest steamer in the world.” The gallery above features glimpses of a dinner menu from the Majestic as well unique amenities and dangers described in the vessel’s first-class passenger list.

Speaking of the Sterns in Coburg, last week the city’s cultural department held a ceremony commemorating the placement of a stolpersteine, or “stumbling stone,” at 10 Mohrenstraße, the address where the Sterns — who were Jewish — resided. Though Jacob’s brother Siegfried, or Selig, and other relatives escaped to the U.S. in 1941, their lives were completely disrupted and upended by Nazi persecution. Like other stolpersteine, the memorial physically forces passersby to remember them.

This Week’s Scenery

Dogtopia: Pensive in Chongqing

This Week’s Detour

Stay on Target: A while back, I was riveted a BBC History Extra podcast episode about the planner of the audacious World War II “dambuster” raid.

I hadn’t known about the May, 1943, raid before, nor had I known a distantly related piece of trivia about how the raid helped inspire the iconic “trench run” in the original Star Wars film. I did know that post-war dramatizations of famous World War II battles and operations had inspired Star Wars creator George Lucas, but until I read this comment, from Reddit user u/meauxterbeauxt (ha!) on the r/starwars subreddit, I hadn’t realized how the 1955 film The Dam Busters helped Lucas imagine the climactic attack on the Death Star by Luke Skywalker and the Rebel Alliance. But the inspiration was made clear by this video Youtube user Henryvkeiper whipped up seventeen years ago.

Dam Wars features footage from The Dambusters with its original audio silenced and audio from Star Wars’s Death Star attack scene in its place. It’s fun and uncanny (and I’ve since discovered that it appears to be one of many such treatments). The similarities between the 1955 film and Star Wars are clear, but like many others have said, the overlap doesn’t suggest a hack job by Lucas. There’s much to critique about Lucas’s creative decisions, including with Star Wars, but I think the similarities to The Dambusters suggest a tribute and inspiration that Lucas built from to spin his own tale, not a ripoff. Still, I now very much want to watch Dambusters.

Next Scenic Route: Love, Light, Music, and Serendipity in the Face of Darkness

P.S. What’s on your current playlist for work, play, or memory? Are there any stories behind your choices?