Quiet.

Loneliness.

Solitude.

These words keep coming back to me when I think about The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, the massively popular open-world video game published by Nintendo in 2017.

Quiet.

Quiet.

Quiet.

I first experienced the sprawling adventure that is Breath of the Wild in the summer of 2020. I set out on that adventure alone, privately, in late corners of the night stolen away from pandemics and bottle feedings, extrajudicial killings and book drafts, tear gas and baby tears, wildfire smoke and sleep training. Those precious moments of escape brought me to a place I hadn’t realized I’d longed to visit, a place of rich detail full of possibility and the promise of freedom. I hadn’t expected any of that in a virtual world, nor had I expected the characteristics of that world that I now treasure most: its quiet and the particular sense of peace that quiet delivered.

I’m the chatty one in my relationship. The loud one, so my partner will probably be mystified by the following claim (as may other close friends and family): quiet nourishes me despite my extroverted tendencies. Only in that cacophonous year when everything changed did I realize this. Actually, even then I didn’t know how much I craved quiet, nor had I yet recognized that I’d turned so often to Breath of the Wild in the months and years following the pandemic’s onset because of the role it played in satisfying that craving.

Of all of Breath of the Wild’s impressive features — the openness of its world, its visual beauty, the flexibility that came with abundant quests for the player to pursue — the impression that lingers most for me is the intentionality of its soundscape. A certain noiselessness pervades the game despite its wealth of creatures, monsters, and characters, and that noiselessness immerses players in the aftermath of a tragedy that has left the land of Hyrule — the game’s setting — ravaged and lonely. The quiet underscores Hyrule’s desolation, but also a resilient, simple beauty persisting despite tragedy to emerge throughout the world should one only look closely. The game balances stillness and dynamism, wits its sound, or lack thereof, often maintaining that balance. I enjoyed Breath of the Wild for many reasons, but I savored playing it because I could get lost in its noiselessness.

I wouldn’t have thought to find such sensory nourishment in Hyrule, which has served as the Legend of Zelda’s primary setting since its 1986 introduction on the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, but that’s where I found it. The world I discovered through Breath of the Wild felt like a place only I knew. It felt like I was the only one there. It was my world.

What made Breath of the Wild so quiet? What did I find in Tears of the Kingdom? Read the rest of this essay at Lascher at Large.

This Week’s Souvenir

For the last sixth months or so I’ve been processing, digitizing, and organizing more than 150 years worth of my famly’s papers, memorabilia, photographs, and other odds-and-ends as part of a larger project. There’s such a wealth of material in this collection of interest well beyond my family (including some astounding photographs of late 19th and early 20th Century California). There’s also much amusement to be found, such as some of the recipes in this electric waffle iron cookbook. Clam waffles anyone?

The pamphlet accompanied waffle irons made by Landers, Frary & Clark, a Connecticut-based manufacturer of kitchen devices with global reach in the early 20th Century.

No, I didn’t find the waffle iron, but I’m opening to making some of the recipes from the booklet with my own waffle maker if there’s enough interest. I’ll probably save the seafood creations until I have paying subscribers willing to stake me in the attempt.

This Week’s Scenery

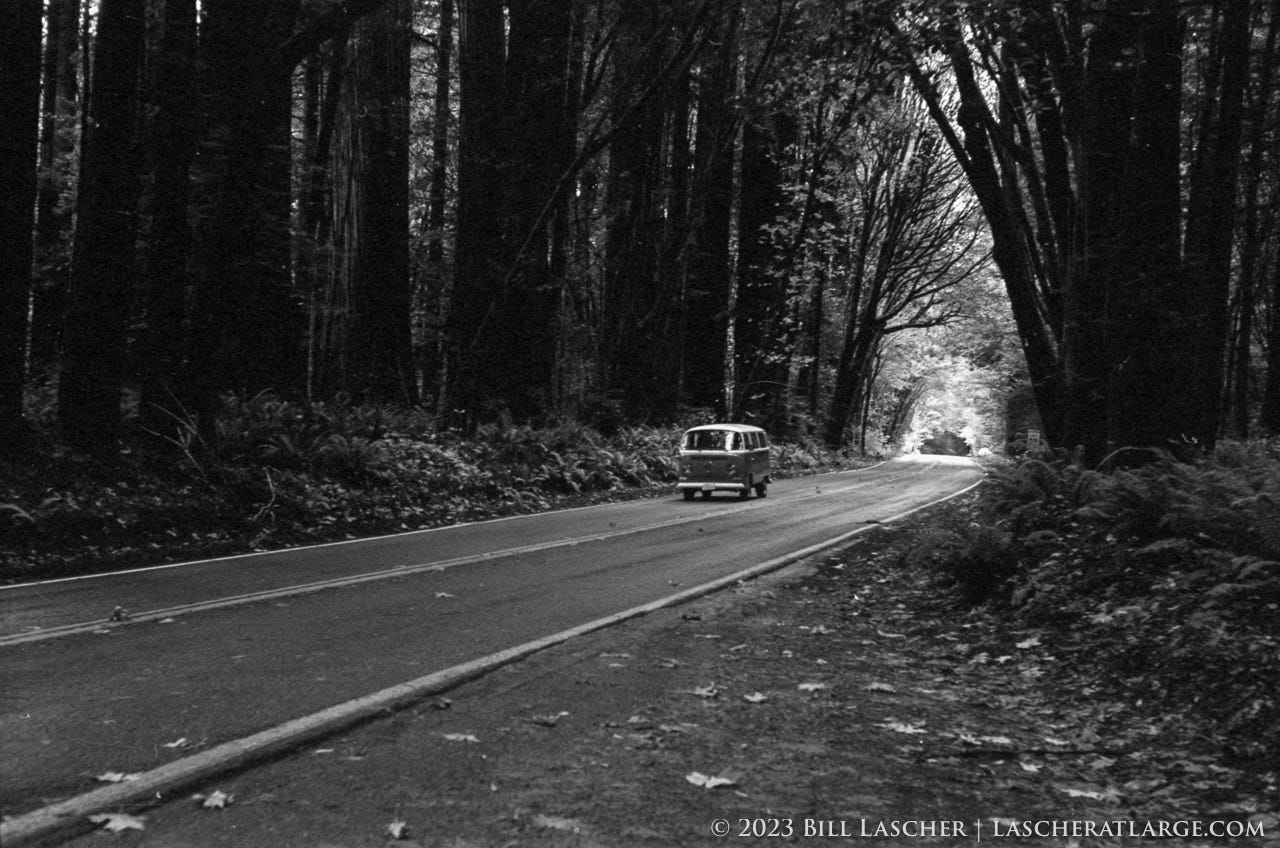

In October, 2016, I gave a reading of Eve of a Hundred Midnights at Stanford University, the alma mater of the book’s subject, Melville Jacoby (whose life I’ve been able to even further flesh out as part of my aforementioned family history project). I decided to drive from Portland to the school for the reading. Naturally, I took the scenic route, which gave me many opportunities play around with my 1930s Contax II rangefinder, the same kind of camera Mel Jacoby used as a foreign correspondent in Asia. Along the way I stopped along U.S. Highway 199 after crossing the Oregon-California border, where I shot this photo of a VW bus entering the Golden State. Though I didn’t know it at the time, as the site of one of sixteen checkpoints around the state where the Los Angeles Police Department deployed armed officers in 1936 to try to prevent Dust Bowl refugees and other poor migrants from entering California, the location would be relevant to my second book, last year’s The Golden Fortress.

This Week’s Detours

While I might retreat to Tears of the Kingdom for more quiet, the onset of Fall in Portland has me eager to turn to “cozy games” like the ones discussed in a recent edition of “The Resties” side-podcast from

My former office mate Rebecca Clarren’s excellent new book The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance came out a few weeks ago, but I haven’t yet had a chance to mention it in this newsletter. Don’t miss it! If you’re in Southern California this weekend you can hear Clarren discuss the book Sunday at the Jewish Book Festival in Ontario and at North Figueroa Bookshop in Highland Park, as well as Monday at the San Francisco JCC.

Having recently completed Reservation Dogs, Lupin, Beef, The Bear, and Somebody Somewhere, my wife and I are craving a new gripping television show to watch. Any suggestions? Fair warning: it feels like we’ve watched nearly everything hyped over the last three years, and anything we didn’t watch we likely tried and disliked. By the way, consider those shows recommendations for you if you haven’t watched them already.

Thanks for reading all this way! I look forward to seeing you along the scenic route, wherever, and whenever, it brings us.

What journeys — literal or figurative — are you taking this week? Let me know in the comments.